This is something I wrote in 2017 right after coming back from my first trip with the OOI cabled array team. Didn’t have the website up then and things got busy, so I forgot about it… 😱

On VISIONS’18, now seems about the time to dust this off. The echogram from the echosounder still looks awesome after a year, so read on! 😎

Watching a solar eclipse is a powerful experience for most people, and that is no exception for those of us who sailed on R/V Roger Revelle during the VISIONS’17 expedition - the annual service cruise to maintain the hundreds of instruments installed on the Cabled Array of the Ocean Observatories Initiative (OOI) network. This year, the eclipse came as we steamed offshore from Newport, OR to the Axial Seamount in the beginning of the third leg of this cruise. However, that morning, the sun was nowhere in sight, as our patch of the sky was completely covered with clouds. But even then, we still experienced the sudden changes of ambient light and the short period of “night” on deck as the moon passed in front of the sun. And we wondered, do the animals in the ocean feel the same difference, and if so, how would they respond?

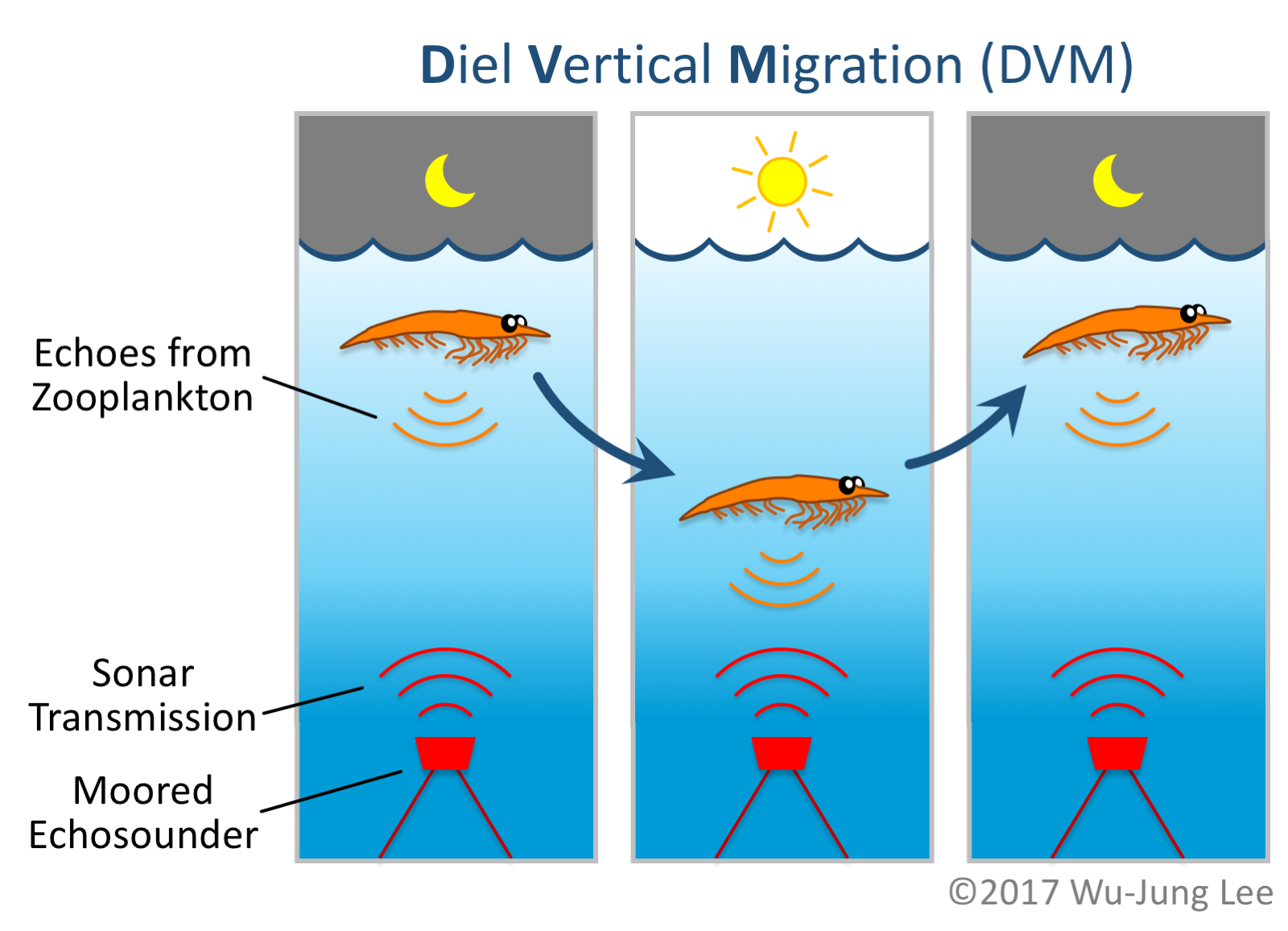

It turns out that scientists have been asking these questions as early as at least the 1950s. Similar to well-known eclipse-associated behavioral changes of terrestrial animals, scientists have found out that many marine organisms respond to the rapid change of light level in a similar way as they respond to the regular cycles of day and night. In regular days, many marine animals ascend from the deep to near the surface around dusk and descend back around dawn, in a behavior dubbed the “diel vertical migration (DVM)”. This is the greatest movement of biomass on earth, happening everyday across the globe ocean. During a solar eclipse, interestingly, many animals respond in similar ways, swimming upward as the light intensity drops temporarily during the time when the moon moves in front of the sun. Other changes, such as significant increases in bioluminescence, have also been recorded. On R/V Roger Revelle, even though we did not carry the type of instruments that would allow us to make the same type of direct observation, we knew that the almost real-time stream of data from the OOI cabled nodes would be perfect for this purpose - especially when several of them are located right within or next to the path of maximum totality!

The moored echosounder on the OOI network can help us observe the vertical movements of zooplankton by measuring their echoes.

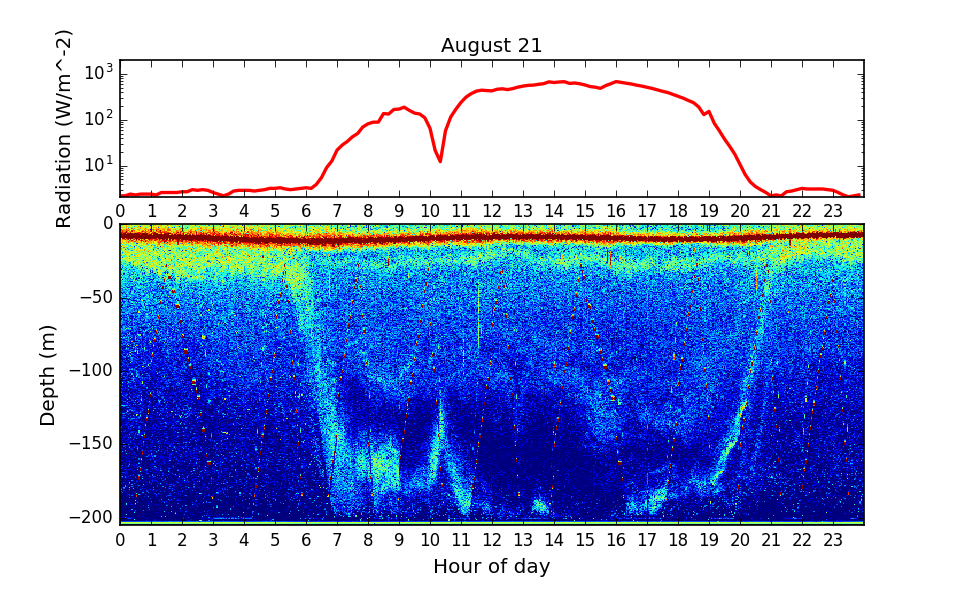

I therefore went straight to the OOI data archive to download data collected by the echosounder deployed on the Oregon Offshore Cabled Shallow Profiler Mooring for the day of the eclipse and the following day (August 21-22). Echosounders are sonar systems that are widely used to monitor the location and abundance of animals in the ocean. They can be installed on the bottom of the ship pointing downward, or, as in the case of the OOI, deployed on the seafloor or moorings and pointing upward. By aligning the returning echoes with appropriate two-way travel delay in the same way as you could measure your distance from a cliff by clapping and listening to the echo delay, we can “see” - through sound - where animals are in the water column. To get a sense of light intensity variation, I found corresponding records of solar radiation from the National Data Buoy Center from a super closeby surface buoy that is also maintained by the OOI team. Here, the data were collected by a pyranometer, which measures the combination of direct and diffuse solar radiation in the 400-1100 nm range.

Solar radiation (top) and echosounder data (bottom) recorded on August 21, the day of the eclipse. The “dip” around 10:15 AM shows the dramatic change of solar radiation level during the time of eclipse. This drop of light intensity induced a “spike” in the echosounder observation due to the brief upward movement of many animals in the ocean.

–NOTE– If you’re curious, here is the notebook I used to create this figure directly from data downloaded from the OOI Raw Data Archive. The notebook included some info about echosounder data processing as well. I am going to dust off this package and the notebook this month during the Oceanhackweek, and will post an update then!

Looking the “echograms,” or sonar images of the water column, compiled from data collected by the 200 kHz echosounder on the cabled mooring during August 21, 2017, I saw just what had been reported in many other eclipses: a large number of animals on their way down to the deep as part of the regular DVM cycle briefly swam upward as the sun dimmed, and continued to descend as soon as the sun was back to its full glare! It is fascinating to see that the variation we saw is almost identical to those observed on Cape Verde Islands back in 1973, using a similar sonar system. Also, the long-term observatory nature of the OOI infrastructure made it super easy to compare animal movement patterns across multiple days at exactly the same location, without confounding factors such as ship movements as in previous studies.

Along with the awe we experienced during this solar eclipse, the fact that I could just download the relevant data sets and observe marine organism responses in almost real-time was an excellent demonstration of the power of the ocean observatory network: anyone from anywhere, if interested, can join in at any time to take a look at a corner of the vast ocean and discover something exciting.

Big thanks to all the people who have worked through days and nights over these past 10 years to make this possible, and of course to the National Science Foundation for supporting this endeavor!